Hello again, devoted fans! We are into tech rehearsals for Lovers’ Vows, and I think it is past time to offer some introductions. Last time we spoke I mentioned our author, the criminally underappreciated Elizabeth Inchbald, and promised that I would at another time give you some greater insight into her super cool life. Well, I am happy to announce that ‘another time’ is Now! Please join me on a whirlwind tour of the life of Elizabeth Inchbald: actress, playwright, novelist, critic, and our current Muse.

Elizabeth Inchbald was born Elizabeth Simpson in 1753, the eighth of nine children, to a Catholic farming family in Suffolk, England. Coming from a large middle-class family she lacked the advantages of a formal education, but was taught at home by her mother and myriad older sisters. She demonstrated an early interest in theatre, in part as a tool to help her combat a speech impediment, but her early attempts to join a local company met with neither family support nor success. Undeterred, she ran away from home at age 18 and joined her brother, working actor George Simpson, in London. In spite of her early failure she was able to make a living on the stage, although her stutter continued to plague her and may have kept her from a breakout success. The following year, at age 19, she entered into a loveless marriage with Joseph Inchbald, an unremarkable actor twice her age with two illegitimate sons who she had met on a previous trip to London [Joseph, not the sons. Well, maybe the sons. But Joseph for sure -KH] and maintained a correspondence and “the strongest friendship” with. This marriage seems pretty obviously to have been one of safety and convenience for her. Certainly a husband in her field would open up new networks and opportunities for her, and having a husband of ANY sort would offer her at least some protection from the unwanted advances of unscrupulous managers and all manner of other creeps. But their significant age difference, the absence of children of their own, and regular arguments about money and Joseph’s drinking and other extracurriculars do not paint a picture of a joyous union. What’s more, every single biography I’ve seen makes a point of how tall, slender, attractive, red-haired, and well-read her and all 5 of her sisters were, and while I’m well aware that love is blind and ‘leagues’ don’t exist, it seems like she could have done better.

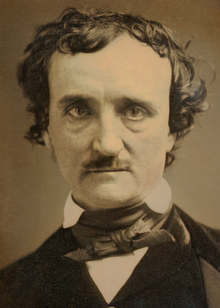

These biographies weren’t wrong. Just strangely insistent I know it. Painting by Thomas Lawrence, 1796.

Having hitched her wagon to the plodding mule of Joseph Inchbald’s career, the two of them toiled in obscurity for some time, working for a touring company in Scotland where Elizabeth honed her talents in ingenue roles such as Cordelia, Desdemona, and Juliet. In 1776 they had the spectacularly ill-advised idea to move to France, where Joseph would learn to paint and Elizabeth would break into the French acting scene. This did not pan out and they were forced to return to England, penniless, after a month, and there join a theatre company in Liverpool. While in Liverpool Elizabeth met actress Sarah Siddons and her brother the soon-to-be-famous actor and manager John Philip Kemble, with whom she would remain lifelong friends. After a few more years of yeomanlike work in regional theatres across the country, Joseph Inchbald had the good sense to die suddenly and unexpectedly in 1779.

His death seems for whatever to have been the trigger that Elizabeth needed. Whether through freeing her from the physical and emotional labor of supporting her husband, or simply by impressing upon her the fragility of life, she began to thrive in the years following his death. She would never remarry and rebuffed many proposals, including from the Earl of Carmarthen, but there was little evidence to suggest she stayed single out of obligation to Joseph. Elizabeth continued to act, in 1780 playing Bellario in John Fletcher’s Philaster [which I mention only because source after source keeps telling me how good she looked in the pants she wore for this cross-dressing role -KH]. But, much more importantly for our purposes, she began to write. In 1784, after years of rejections, one of her plays (The Mogul’s Tale; or, the Descent of the Balloon) that she wrote under an assumed name saw production and success at Covent Garden. She promptly owned up to it, presumably causing spit-takes and popped-out monocles across the nation. Once the seal was broken and her bona fides as a writer established, her career rapidly progressed, writing almost twenty plays (among them our own Lovers’ Vows) and two novels in the 1780s and ‘90s. [These novels, A Simple Story and Nature and Art, are apparently what she is best known for, but we here at We Happy Few are hoping to change THAT -ed.] By 1789 she was successful enough to retire from the stage, enter high society, and make her living entirely as a playwright, and by the end of the century she was able to retire from THAT and live solely as a critic and socialite.

Inchbald regarded it as an obligation to turn critic and editor, believing that she owed something to the theatrical community which had given her so much. She seemed to have taken that obligation seriously, writing for the well-respected Edinburgh Review, and in 1806 she was commissioned by the publisher Thomas Longman to write introductions for The British Theatre, a series of 125 plays from the 16th-18th centuries, a substantial honor and vote of confidence for any playwright. Not content to run solely in theatrical circles, she was a well-known feature in London’s social and philosophical scene and counted among her friends author Maria Edgeworth, journalist and notorious Jacobin Thomas Holcroft, the aforementioned John Kemble, and noted philosopher [and the father of We Happy Few’s goth mom Mary Shelley -KH] William Godwin, with whom she had a nasty and confusing falling-out in the late 1790s over his marriage to Mary Wollstonecraft, of whose affair and child with noted American creep Gilbert Imlay Inchbald did not approve.

In her final decade Inchbald turned inward, retreating from high society and rediscovering her long-neglected Catholic faith. She maintained correspondence with her friends, especially Maria Edgeworth, and worked on her memoirs which have unfortunately been lost to the sands of time (or, specifically, the flames of her confessor, who unaccountably advised that she destroy them), but spent much of her time in contemplative seclusion. She died in 1821 at the age of 68.

My main takeaway from Elizabeth Inchbald’s life, aside from that she is incredible and that everyone should know her name and her work, are the virtues of persistence and tenacity. She overcame parental disapproval and a speech impediment to achieve her dream of acting professionally, made the best of a bad marriage to hone her theatrical talents, didn’t take ‘no’ for an answer until she got her plays and prose published, and wedged herself into an artistic and societal niche that she then forced open so wide that fame, fortune, and respect could not help but fall in. That her name is not as well known as Jane Austen, Ann Radcliffe, the Brontë sisters, Mary Shelley, or her own friend Maria Edgecombe as a formative writer of the late Georgian period is an unaccountable flaw in history, and it is my sincere hope that our production of one of her finest works will do some small part in restoring her name to the theatrical consciousness. If you’d like to assist me and my colleagues in this idiosyncratic venture, please purchase tickets HERE and join us!