Happy Halloween, everyone! Blogslave Keith Hock back again to share some more spooky scary horror thoughts with you before the Halloween Bell rings and I turn back into a pumpkin […right? My personal mythology is getting a little muddy -KH] and have to go back to talking about staging and lighting and direction and all that, you know, actual theatre stuff on this blog I write for a theatre company.

But before that happens I have one last horror trope discussion that I want to squeeze in, one that each of our three shows touches on differently: solitude. I’ve touched on this topic once before, but only in passing, and it was a LONG time ago. I think it’s about due for a deeper exploration, wouldn’t you say? Ordinarily I would invite you to join me on this journey for a little while, but it would be counter to my theme this time. So instead I will ask you to focus on the fact that you’re reading this by yourself. No one is with you. If you’re at work, everyone else is at their own desks, working on their projects or goldbricking like you, by themselves. If you’re on the train or the bus, even if you’re pressed in with people, each and every one of them, yourself included, is alone. Headphones crammed in both ears, eyes locked on your phones, willing away the sensation of being surrounded by strangers. Maybe you’re at home, sequestered from the dark chill outside, turning on all the lights so you don’t get sad and desperately clinging to whatever Netflix show you half-watch for company and noise, any noise to hide from the cold, mechanical tick-tock of that old-fashioned clock that you don’t remember buying or hanging up [whoa, lost the thread a little bit there. Let’s rein this back in. -ed.] Anyway, meditate on the intense loneliness that permeates modern life while we explore isolation in horror.

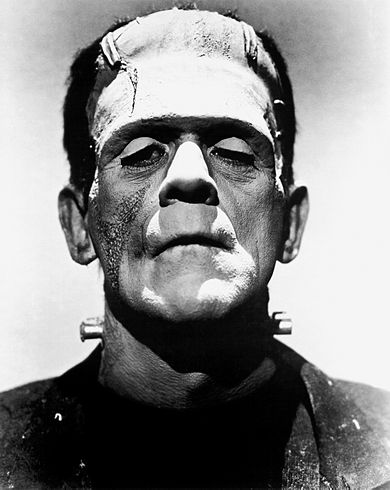

Scott Whalen, from WHF’s 2018 production of Frankenstein. Photo by Mark Williams Hoeschler

Let’s start from the same place I started oh those many moons ago, when we were adapting our first Poe story. At the time I called out how uncommon it was that Poe would write a horror story that could so easily be rendered as a dialogue, because it suited our purposes from a staging perspective. And I had some, frankly, pretty stupid and poorly-written ideas about what made horror such a solitary genre. If I somehow had even less integrity than I already do I would have secretly edited that paragraph so that I sounded less dumb and had a halfway-coherent thesis. But instead I will leave it as a monument to the ignorance of youth, and will make some more bold and poorly substantiated claims here which certainly I will not be embarrassed to look back upon in another three years. Only this time, instead of broad generalizations about horror as a whole (which I have saved for my dramaturgy notes) I will observe solitude through the lens of our three adaptations, to see how different authors interpret this necessary facet of their genre.

In Dracula, solitude equals vulnerability, straight up-and-down. Lucy, Mina, and Jonathan are in the most danger when they are alone, separated from their allies. This should not be surprising for a book that is more transparently about the power of friendship than Harry Potter, a book series so transparently about the power of friendship that the seventh book opens with a quote about how the bonds of friendship are so powerful that they transcend death itself. Dracula prides himself on his hunting prowess, comparing himself to a wolf. But his wolf-lore is lacking, because he failed to notice that wolves hunt in packs. Once his prey are able to join together and work as a team they quickly turn the tables on the Count. The message is clear: while the world may be full of mystery and danger, there is no challenge that cannot be overcome with friends.

L-R: Kerry McGee, Jon Reynolds, and Meg Lowey, ready to hunt some vampires.

Poe seldom used isolation as a theme in and of itself. He often used it as a symptom of sorrow, as in The Raven or Annabel Lee, or simply as a condition, a necessary precursor to the story he wanted to tell; for The Pit and the Pendulum to work the protagonist must be by himself, but his solitude doesn’t MEAN anything ulterior to the text. But most frequently for Poe, loneliness was closely associated with madness, though which one led to the other is not always necessarily clear and varies from story to story. Considering that Poe’s personal life was rife with personal tragedies, loss, and betrayal, it makes sense that he would be both desperate for, and suspicious of, companionship. Perhaps the best example is The Tell-tale Heart. Our murderous ‘hero’ at first seems to be driven mad by the mere presence of his elderly roommate, and then, if possible, driven even madder by his absence. Unable to tolerate either companionship or isolation, his unraveling mirror’s his author’s, and the reader’s, struggles to find their place in the human community.

Frankenstein is more explicit about the theme of solitude than Poe, for whom its meaning varies depending on the demands of the story, and more nuanced than Dracula, where it is directly refuted by demonstrating the importance of friendship. For Victor Frankenstein solitude brushes perilously close to solipsism. He needs to be alone while he works, he cannot bear Clerval’s presence or respond to his father’s letters. Even his wedding night he spends by himself, scorning his bride in a misguided attempt to outwit his far more cunning Creation. Frankenstein erects countless barriers between himself and the people who care about him, in the name of keeping them safe from his ‘tortured genius’. Contrast this with the Creation himself, an actual tortured genius who would love nothing more than simple human contact but is stymied by the cruel accident of his birth. Victor scorns the love that is heaped upon him at every turn in his arrogant pursuit of solitude, while his Creation, cursed to an eternity of isolation, hunts desperately for any sort of companionship or, indeed, attention.

If you would like to have friends to help keep you safe and sane from the encroaching darkness that typifies the human condition, why not invite someone to come with you to see one (or all) of our shows? We are running until the 10th of November, and tickets, though going fast, are still available! I hope to see you there!