Hello again! Sales have begun for the second episodes in our highly popular and well-regarded Detective Audio series, featuring the cunning Sherlock Holmes and the irrepressible Loveday Brooke, and you all know what that means! It means I’m back to talk some more about whatever fool idea comes into my head, to pique your interest in those same audio plays and to hopefully encourage you to purchase them [they make great holiday presents! Just ask my entire family at the end of the month -KH] [But don’t tell them -KH] This time that topic will be a continuation of my series on detective stories. Last time we talked about their pedigree, where they came from and who begat whom, as well as a quick gloss on the variant forms they can come in. Today we will discuss what makes a detective story tick; the rules, both unwritten and thoroughly codified, that people have imposed on the genre. What’s more, last time we spoke I made you all a promise, if you’ll recall. Now a promise made is a debt unpaid, as I learned from my grandfather from his recitations of The Cremation of Sam McGee at family reunions, and I promised last time I would more thoroughly unpack the wide variety of subgenres and offshoots that can trace their origins back to the Detective story.

As I mentioned last time we spoke, our heroes, Sherlock Holmes and Loveday Brooke, are early figures in the history of the genre. Though not the first, Holmes is unquestionably the most famous detective in literature and laid much of the groundwork for future stories. Loveday Brooke is a contemporary of his, and while being both a woman and a working-class detective are noticeable departures from the norm, neither of those facets noticeably impact her sleuthing or the kinds of mysteries she is called upon to solve. Neither of our characters deviate from the classic Detective in the classic Detective story, in any of the myriad ways we will soon explore that a story can. In fact they are in many ways what their descendants are reacting to and turning away from, in their feverish propagation of new kinds of mysteries and new ways to solve them.

But before we delve into THAT topic we have to determine what makes a Detective story. Unlike pornography, which can only be identified on a case-by-case basis, there are rules that a story must follow to fit into the genre. Obviously there must be a detective character of some sort. Equally obviously there must be a crime or mystery for them to solve, otherwise it is just a boring naturalist story about a detective buying groceries or whatever. The detective must have some sort of assistant or sidekick audience-surrogate figure to bounce ideas off of [N.B. this character can but does not HAVE to be the same person each time; Holmes has Dr. Watson but Hercule Poirot gets dealt a random police lieutenant or family friend or former associate for every mystery -ed.] And not strictly mandatory but ubiquitous enough to bear mention is an upper/upper-middle class backdrop to the story, an environment of money and Society which explains not only why all of the suspects have time to answer questions from a nosy detective for several days, but also how they can afford to retain a consulting detective and why they would like to keep the incipient scandal under wraps, and the pots of money floating around keeps the “stands to inherit/debts to cover” motive in play. There is a reason that the traditional setting for a murder mystery is a party at a manor house.

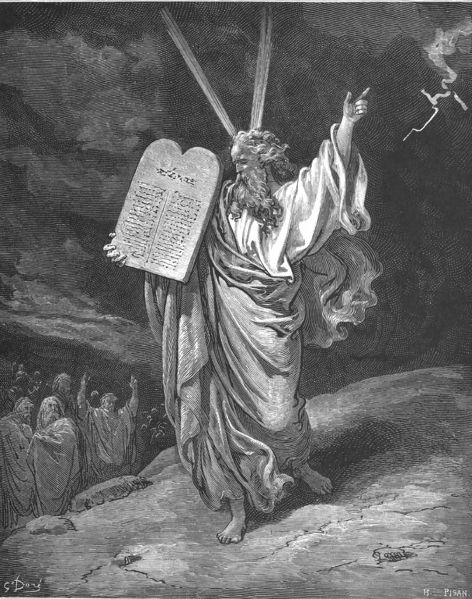

As the years passed, and the detective story became more and more popular, this bare set of rules was deemed insufficient and more stringent qualifications were proposed, ostensibly to maintain the high quality of story that the reading public demanded but serving mainly (in the nature of gatekeeping requirements everywhere) to limit the playing field to the “appropriate” kinds of stories and writers. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Golden Age of Detective Fiction, a number of authors wrote guides attempting to codify the tenets of a proper Detective story. Two of those authors, S.S. Van Dine and Ronald Knox, went so far as to create enumerated lists to be followed, Van Dine’s Credo of 20 rules and Knox’s Decalogue (or the Ten Commandments of Detective Fiction). Some of these rules seem reasonable for making the stories “fair” (that is, solvable) for the audience; rules like No Twins, No Hunches, Only One Secret Passage, The Killer Has To Be Introduced Early, and The Killer Can’t Be The Detective. Others were more of a stylistic preference, like No Romance, The Crime Must Be Murder, No Supernatural Elements, No Conspiracies, The Sidekick Has To Be A Little Dumber Than The Audience, and No Literary Pretensions Distracting From The Mystery. And then some were just downright offensive: The Killer Must Be A Person Of Quality, Not A Servant or No Chinamen [in fairness to Ronald Knox, his complaint was a reaction to the use of Yellow Peril stereotypes in the stories of his contemporaries, not a personal antipathy. But still, not the most sensitive of rules -KH] Regardless of their intentions these rules, if assiduously followed, would have an enormously chilling effect on the form; a seasoned reader may note that many of these requirements would disqualify a number of Sherlock Holmes stories and, if practiced in toto, would reduce the burgeoning detective genre to little more than a category of especially prolix logic puzzles.

But more germane to my current thesis: you don’t ban something unless there is a reason to do so. These rules came into being as a reaction to the sorts of stories being written. And the writers of those stories, unsurprisingly, felt no particular need to obey these commandments, but rather continued to tell the stories THEY were interested in telling. Many of these stories have, justly or wrongly, disappeared from the public consciousness [or at least from MY sphere of awareness and light research for the purposes of writing this post -KH] but the influence they must have had is as clear as day in the existence of their descendants, clearly utilizing some of the structure of the detective genre while embellishing in some way to create their own form.

One of the earlier offshoots, occupying a unique position, is the rise of child and Young Adult detectives. If you’ll remember from my discussion of Treasure Island, YA fiction (in my calculus) is not quite its own form but a subgenre of the corresponding adult fiction genre, with some changes meant to aim the stories at children. Take for example Leroy “Encyclopedia” Brown, the power behind the throne of the Idaville police department. Encyclopedia Brown doesn’t follow hunches that happen to be correct. He doesn’t conceal his thinking from the audience or his Watson, bodyguard Sally Kimball. His nemesis Bugs Meany may be the leader of a gang, the Tigers, but it isn’t a hidden secret society, and never do his solutions hinge on hidden doors or body doubles. No doubt S. S. Van Dine would approve, if only Idaville had been filled with the tiny broken bodies of murdered children for Brown to investigate, instead of missing baseball cards or rotting pumpkins.

Brown was just one of a host of child detectives, all solving age-appropriate mysteries with more or less of the appropriate rigor for our Arbiters of Quality Messrs Knox and Van Dine in their investigations. Some of the older children, such as the Hardy Boys or Nancy Drew, experience rather more adventure in their adventures; seldom does a Nancy Drew book go by without a chapter titled “Kidnapped!”, and Frank and Joe brawled with more than their share of smugglers while unravelling the mystery of Pirate’s Cove. But one set of detectives stands out in the catalogue of child detectives for more than just toeing the line between mystery and adventure story.

Setting aside their talking dog for a moment, Fred Jones, Jr., Daphne Blake, Velma Dinkley, and Norville “Shaggy” Rogers almost exclusively solved mysteries of a supernatural nature; ghosts and Bigfoots and haunted robots who were trying to steal from museums or defraud amusement parks or smuggle gold. While the true culprit was always some elderly malcontent in a rubber fright store mask, the story was always oriented around unravelling the meaning of the supernatural doings plaguing the town. Nor were they the only child sleuths with a mystical facet to their stories. Ghost Writer, of the eponymous show, was a ghost under a curious curse that only allowed them to interact with the material plane to highlight and interact with words and letters, and who (naturally) used these powers to aid a multicultural group of Brooklyn teens in solving mysteries, perhaps in hope of accruing enough good deeds to be freed from their eternal torment and allowed to rest.

While our Mystery Authorities, Knox and Van Dine, would surely choke on their pipe smoke at the spooky silliness and lack of solvability of all these stories, they certainly hold to at least the spirit of a detective story, which cannot truly be said for my next topic: NON-child-oriented supernatural mysteries. Or perhaps I should just directly say Adult Supernatural Mysteries, because these stories seem, for whatever reason, to veer quickly and heavily into Supernatural Romance. Charlaine Harris’ Sookie Stackhouse novels, the basis of True Blood, are officially titled the Southern Vampire Mysteries, but a more accurate description for them would be Vampire Action Erotica. Also fitting into this category would be the Anita Blake books by Laurell K. Hamilton, about the Federal Vampire Executioner of Saint Louis and her dangerously inaccurate experiences with the Monster BDSM community. Lip service is paid to the idea of a mystery to solve, but the main focus of these stories is less meticulously investigating, collecting, and evaluating clues, and more putting the main characters in mystical peril and finding them ever-more-beautiful men to sleep with. Though in fairness, any story involving vampires has to work pretty hard to not become a SEXY story involving vampires, as I have addressed in the past.

Anita Blake at least does have SOME structural bones in common with yet another subgenre of detective fiction that has blossomed into its own form; the Police Procedural. The Police Procedural, which you will probably most recognize from your sick days when you’re bored at home and turn on TNT and watch ten straight hours of NCIS, asks a novel question of the audience: What if there WASN’T a preternaturally clever Consulting Detective available to leisurely crack the case, and instead it was just Lestrade and his companions on the police force, doing their level best to solve it with their regular human brains, collaboration, and a lot of legwork. The focus, as you may have guessed from the name of the genre, is on observing the day-to-day procedures of a police department as they go about their investigation, conducting forensic studies on the crime scene, following up on leads, conducting interviews and interrogations, sometimes all the way up to testifying in the trial. These stories are not generally about proving the cleverness of the detectives and by extension the audience for cracking a difficult case, but rather showing a still heightened but more realistic depiction of the process by which actual criminal investigations take place. Knox and Van Dine would surely have barely considered these stories as worthy of the name detective fiction, being so concerned with the crass and contemptible world of the lower and middle classes.

Harry Dresden of the Dresden Files, despite being Chicago’s Only Wizard P.I., also managed to dodge being tarred with the same Vampire Action Erotica brush as Ms. Stackhouse and Ms. Blake. His series is, first of all, less sexy than those books, which is pretty remarkable for a series in which a prominent recurring character is an incubus. And second, Dresden may be a wizard, but he is also a hard-boiled detective, and hard-boiled detectives are SUPPOSED to get into fistfights and have guns pulled on them. Hard-boiled detective stories approach their mysteries the same way that police procedurals do, with legwork. The only difference is that hard-boiled detectives don’t have the institutional resources of a police department. Hard-boiled detectives solve crimes with brute force, both the mathematical concept and the literal use of physical strength. Philip Marlowe, Jack Reacher, Jake Gittes, and the nameless Continental Op aren’t smarter than the reader, as many literary detectives are. They’re just more cynical, having earned their mistrust the hard way with years of witnessing the worst humanity has to offer in their dogged pursuit of the truth, both on the dusty streets of Poisonville and in the seamy underbelly of high society. Their (oft-broken) nose for clues and savviness about the hunt would surely entertain our pals Knox and Van Dine; Philip Marlowe carries around exotic grass seeds, foreign cigarette butts, and matchbooks from bars he’s never been to, to sprinkle around crime scenes and baffle forensic examiners. But the detectives’ insistence upon falling in love with every pair of legs that walked through their glass door is a clear violation of their No Romance rule.

And finally here we come to the final mystery subgenre with which I am enough acquainted to discuss, the Cozy Mystery. If we were to recategorize the stories from the Golden Age of Detective Fiction, this is where they would most closely fit. Cozy Mysteries are stories about isolated, unexpected crimes visited upon small, quiet communities, either where the detective lives or happens to be visiting. The detectives may be a retired or independent sleuth themselves, like Poirot and Ms. Marple, who conveniently happens to be in the neighborhood, or they may be simply talented amateurs, such as novelist Jessica Fletcher of Murder, She Wrote or Father Brown. While the crimes in question are often murder [meeting with the approval of our Review Board –KH], they are only ever discovered, never witnessed by the audience, and are none too gory, gruesome, or shocking. There is seldom any romance to speak of, and any that occurs is typically on the chaste-r side. The world and characters tend to be soft and a little quirky, without being out-and-out wacky or bizarre. The stories engender a calm, safe, warm, comforting…frankly, Cozy feeling when read or watched. They play fairly closely to the rules of the Game as set out in the Golden Age, with the exception that the aim is less to challenge the reader to compete with the detective (and through them the author) and instead to relaxingly follow along with the detective as they piece the puzzle together.

But our detective stories don’t fit into any of these categories. Sherlock Holmes and Loveday Brooke predate even the Golden Age writers, and are not bound by their rules. Certainly they, like many of their colleagues and descendants in the pure detective line, fall closest to the Cozy Mystery as well, but their world is too broad and their dangers too real to exactly fit the bill. Their adventures transcend subcategorization, and must be experienced to be truly appreciated and understood. Fortunately for you there is still time for you (and your loved ones!) to appreciate these before the holidays! All four of our packages, both current and previous adventures for Sherlock and Loveday, are available now! The sooner you order them the sooner we send them, and the better your chances are of them arriving for Christmas!