Welcome back, everyone! It’s been a while! I’m sorry to abandon you all winter, but, like a bear, We Happy Few needed to take the winter season to hibernate. We are rejuvenated along with the cherry blossoms of our fair city, though, and we are ready to begin preparations for our Spring show. We Happy Few are very excited to bring you all Pericles, Prince of Tyre this season! Tonight is our first rehearsal, which means while everyone else is working very hard in the rehearsal room I get to write about whatever oblique or tangential angle I can find on our play, and then find a way to connect it to our concept. To that end I am looking forward to answering your questions about this comparatively little-known play, starting with “What and where is a Tyre?”

Tyre is a city that used to be an island fortress off the coast of what is now Lebanon. Besides this play it is known for being the birthplace of legendary Carthaginian queen Dido and a stronghold of European crusaders in the 12th and 13th centuries. But it is perhaps most famous for its defiance of Alexander the Great and his…creative response.

Art by Adam Hook, for Ancient Siege Warfare, by Duncan Campbell

Remember how I said earlier that it was once an island? It was actually barely connected to the land by an extremely narrow sandbar which was submerged in water most of the time. This placed the city in an unusually good defensive position when Alexander came a-calling on his mission to conquer the world, and the Tyrians were accordingly disinterested in his overtures. So disinterested, in fact, that they killed his emissaries and threw their bodies off the walls in plain sight of Alexander and his army. Not one to take an insult lying down, and demonstrating his famously pragmatic problem-solving, Alexander ordered the sandbar be enlarged and built up to a causeway allowing his army to march up to the walls and besiege them. This was STILL not enough for the Macedonians to conquer the city, as naval sorties kept his siege engines from making any headway until naval reinforcements from Greece eventually gave him control of the waves and he was finally able to conquer the city. In retribution for their arrogance in fighting for their city and lives he crucified 2,000 and sold the rest of the population into slavery, and then to add insult to injury left his causeway in place. It connects Tyre to the mainland to this day.

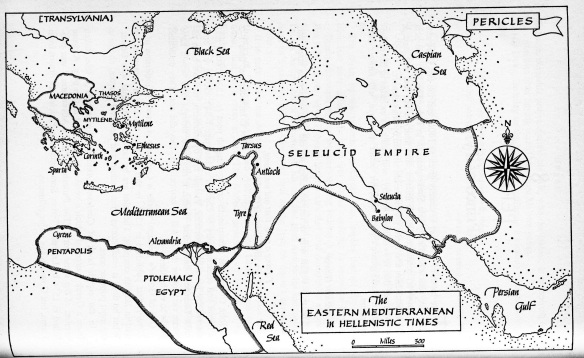

You may notice that I did not spend a lot of time actually getting into what is significant about Tyre and why Shakespeare (and George Wilkins [I’ll get to THAT another time-KH]) chose to set this place here. To address that briefly: the obvious and boring reason is that the story Shakespeare plagiarized from Gower based it on, Apollonius of Tyre, dictated that it be so. But like I said that’s not especially interesting, and as you can probably guess from my primary conceit in most of my other blog posts I have something else in mind. Pericles, despite the title of the play, spends comparatively little of his time in Tyre, mainly sailing between and having adventures on and around a handful of islands and ports in the eastern Mediterranean. He ventures to Mytilene and Ephesus on the Turkish coast, to Tharsus and Antioch in the northern Levant, and all the way down to Pentapolis in modern Libya.

Illustration by Rafael Palacios, for Asimov’s Guide to Shakespeare, by Isaac Asimov

But you won’t find me putting too much analysis into why he visits any of those cities, either. To my mind there is nothing overly significant about any of these locations individually; the important element to examine is the overarching setting of The Mediterranean, or to be even vaguer, The Sea. It is no accident that at different points the story is driven by not one but two distinct storms and a pirate raid.

Rough Weather in the Mediterranean, by Henry Moore, 1874.

And if the physical setting is meant to be vague the timing can be even more so. According to Isaac Asimov the presence of a King Antiochus the Great in the text vaguely establishes a time period of around 200BC, but since there never WAS a Pericles who ruled Tyre the timing can afford to be up in the air. Asimov also whines that ‘Tharsus’ doesn’t exist and is either a bastardization of Tarsus or Thasos, or an entirely made-up city-state, so its possible he was a little overly-concerned with the verisimilitude of this clearly fantastical play. This isn’t a history, like Henry V or Anthony and Cleopatra, where the time period is integral to the play and can be authoritatively nailed down. It is closer to a legendary ‘history’ like Cymbeline or Troilus and Cressida, that has a vague timeline but would be best categorized as ‘A long time ago’ or ‘Once upon a time’. If we must nail down a specific era the only timing that matters is that there be no hegemonic control in the region; for the plot to work all of the city-states, Pentapolis and Antioch and Tyre and Tharsus and Mytilene, all be independent and free to backstab and politic. That means it would have to be either after the Peloponnesian Wars (ended 404 BCE) and before the rise of Alexander the Great (330s-320s) or between the disintegration of Alexander’s empires (~300BCE) and the rise of Roman authority in the Near East (let’s call it 30BCE). This is without even taking into account anachronisms like Transylvanian whores and French johns and Spartan knights with Latin mottoes and clocks […not clocks. Wrong play again, sorry -KH]. The specific time period doesn’t seem to have been especially important for the story that Shakespeare wanted to tell, or we would have a more concrete textual sense of it.

This is not to say that we are meant to be kept off-balance or confused by the setting; only that we are not to put TOO much weight on where the action is meant to be. Pericles and the entire play are constantly in motion, and while I would argue that the Mediterranean/Greek/Hellenistic setting is important (for reasons I will ALSO discuss in a later blog) the continual, overwhelming, and above all unpredictable nature of The Sea is essential to the constant upheaval that typifies this show. I look forward to talking your ears off about this play for the next month until you all agree with me, and then continually bragging about how good it is after it opens in May. Won’t you join me?